When the 1% actually writes about what it knows: "Quiet Street" by Nick McDonell

Or how America’s 1% compares to Russia’s 1%…

I think I’ll start writing about books more. If I had any religion growing up, it was literature. I was an only child with a working single mom and spent a lot of time alone reading. Since my mom is an atheist, I didn’t have any religious indoctrination about how to live my life and how to behave, so novels did offer certain answers instead.

This is a longwinded way to say that I think it’s good to have a kind of a book club here that helps people weed through so much noise and overproduction of garbage that is pushed on us daily, and to focus on things that are worth your time, which is increasingly harder with all the digital distractions.

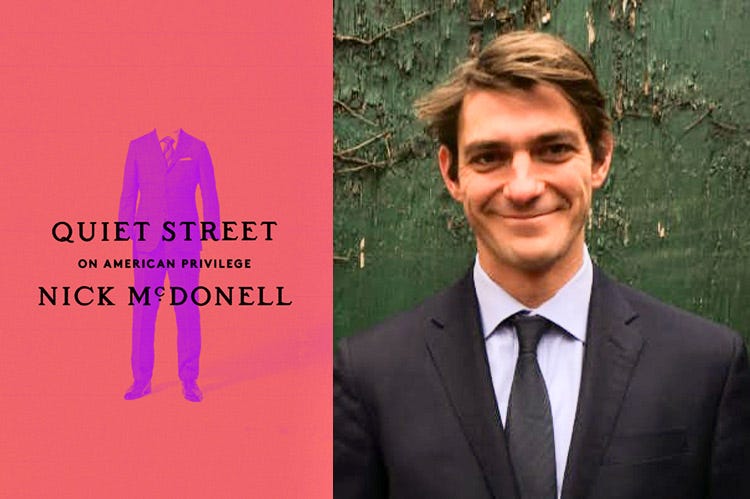

I’ll kick off this series not with a novel, but a great nonfiction book that does read like a novel. Quiet Street: On American Privilege by Nick McDonell.

It’s taboo to talk about class in America, since this is a supposedly meritocratic society where anyone can become whatever they want with enough determination and hard work. The existence of an entrenched class system is not comme il faut to focus on, and it is exactly what Nick McDonell does in Quiet Street. The book got a few (and somewhat lukewarm, if not derisive) reviews from the liberal media — even though it is very well written and deserves the praise that many other memoiristic essay collections often get. The reason the book’s been basically panned is because I think he struck a cord with precisely the type of media people who don’t want you, the reader, to know that they had a leg up in the literary world. They made it all on their own.

It’s rare that someone from McDonell’s world of moneyed New Yorkers has the sensibility and enough detachment to see and examine his own environment. If people from that world become cultural producers, they usually don’t look at themselves or their own class, and instead make films and tell stories about faraway places and people that are poor. Nick, on the other hand, just tells stories from his life — his time at Buckley, an all-boy Upper East Side prep school, his trip to Galapagos, his friend Clarissa Ward who got her journalistic internship in Moscow for CNN arranged through one phone call though her mom’s dentist, his first book deal at 17 arranged through his dad, another one because he happened to stay at an exclusive resort and got to talking to a Hollywood producer, etc. You know, normal stuff.

What Nick describes is a dreamy kind of life where kids are nurtured and encouraged to develop many skills and to follow their passions in the style of a renaissance man. Yet as Nick reports, most people in his milieu end up in finance — so much for all their renaissance man upbringing.

Nick does stand out as he admits himself. He is on the poor end of the 1% and his dad is not not old banking money, but a boomer success story: Terry McDonell rose to be a mangling editor of Sports Illustrated and joined the Manhattan literati elite. So Nick followed in his dad’s footsteps, becoming a second generation novelist and journalist. Maybe because he didn’t come from entrenched wealth he could see the oddity of it all.

In any case, his attempt to examine his class and his own privilege — a privilege that helped him find literary and financial success early in life — is impressive and laudable. He wonders whether it was just pure merit that allowed him to publish his first novel at 17, a novel which then got adapted into a Hollywood film directed by Joel Shumaher. Is he that good? Is he that brilliant? He has his doubts.

The fact that he openly talks about his entitlement seems like it goes against the grain of the anti-woke vibe shift happening in Manhattan’s literary world, where talking about morality, social responsibility, inequality, and systemic injustice is seen as cringe and lame. “The enlightenment project is dead,” haven’t you heard? McDonell clearly didn’t get the memo.

I could relate to the book in an unexpected way. I grew up in Moscow in the 1990s/2000s and studied in one of the best high schools and then at Moscow State University, just like my parents. And it’s funny how similar my experience is to what Nick describes in his book. We were told in my high school that was called lyceum (and by the way it was a public school since they all were, good and bad ones) we are the elite of our country, we would be taken to the Duma to meet members of parliament, and we also learned poetry by heart so we could send signals to others about our class. We were taught to be polite, well mannered kids with etiquette for positions of power. At my high school, you could learn not only English, French, and German, but also Chinese. You could take philosophy and journalism classes, have media internships.

I was never rich. My family was just part of Moscow’s old intelligentsia. My dad was a poet, my mom was a literary editor. They didn’t have much money but the access they had to cultural institutions was definitely a form of capital. In that sense, the world of indigenous Muscovites was like Nick’s old money world: entrenched and small and connected — knowing people, having easy access to education and careers and opportunities. Things for which others had to fight and struggle were available to us with much less effort. At the same time I was surrounded by the kids of nouveau riche Russians. They got access to these top cultural institutions in the 1990s and some were very wealthy. But they were often uncultured and still deferred to the old intelligentsia. During the transition from socialism to capitalism wealth and high culture often didn’t align like it does in Europe or America. You could be very cultured and very poor. Or insanely wealthy and barely educated. But that’s all coming to an end now. The kids of these nouveau riche have gone to the best schools and so Russia is now becoming more like other “normal” societies — societies that didn’t have revolutions that got rid of their one percenters.

Either way, in my experience both the nouveau riche and Soviet intelligentsia lacked any idea of noblesse oblige that Nick describes being drilled into him and his classmates in school. In similar circles in Moscow they would find the idea of noblesse oblige preposterous. And the disdain for the common and poor people was much more open, which is ironic considering it was a socialist or recently socialist country. But it also makes sense: the people who suddenly found themselves in the positions of new nobility in post-Soviet Russia were still too close to the peasants that were below them. They were the peasants — peasants who got lucky or were particularly ruthless and enterprising.

In the upper class New York world that Nick describes there was at least a layer of civility — at Buckley they were taught to live according to a line from Luke 12:48: “to whom much is given, much is expected.” Well, at least in theory. In practice, people from his world rarely interacted with people outside their class — unless they were their servants, nannies, and teachers. And they called the non-white people working in their school cafeteria “wombats” and then after school pretended to be black gangbangers who tagged and flashed made-up gang signs to each other.

The book really made me ponder what is worse: a quasi-meritocractic society that pays lip service to egalitarianism, and at least says the right words and preaches good things to the public… or one that’s rigidly hierarchical, where might makes right and where the rich flaunt their privilege and power over everyone else and uphold no Enlightenment values.

The Soviet Union was supposed to be the first radical egalitarian society that would create a “new man,” and it did succeed to an extent. Participation in high culture and leisure activities like music, painting, dance, and ballet was free for anyone interested whether you were a kid of a cleaner or an architect. But USSR also created a “red bourgeoisie” — members of the politburo, the central committee, and various party apparatchiks who had their own hospitals, schools, and vacation places. Their lives were obviously not nearly as ostentatious as those of the rich and powerful in the West. But in comparison to the life of your average worker or collective farm peasant it was a real unbelievable luxury — hospitals with marble staircases and red carpets, concierge doctors, big apartments, chauffeurs, maids, country houses. I saw a bit of those places in the 1990s because my mother took a government job during the Yeltsin years, which gave us some access to this old red bourgeoisie world — a world that my mother only peripherally knew when she was growing up.

Of course this Soviet hypocrisy is not good. But I myself only got to experience the post-Soviet nihilism that came to replace it, and the lack of civility and cynicism and open violence and hatred of the poor was pretty horrible to witness. And I felt quite alienated from it, and I never wanted to stay in Moscow because of it, despite all the opportunities I had.

Weirdly enough I feel like I have culturally more in common with someone like McDonell, even though he is a one-percenter form Manhattan, than most people from my world — not just the progeny of the Soviet Muscovite intelligentsia but also the nouveau riche Russians who only care about consumption and luxury items and launch their own designer boutiques or some other useless businesses in Moscow, or at best open art galleries unable to envision anything better to do with their time and money.

After the collapse of the USSR the rich in Russia were not interested in cultural production — because until recently there wasn’t a lot of money or prestige in it. That’s why people who became filmmakers or writers or artists often didn’t come from this newly rich class. At least this was true in my generation and the one before me. So there is practically no one who can actually report from that world in the funny and insightful and honest way the way McDonell does. There are no whistleblowers like him among the Russian 1% — which is very telling about where Russian elite is at spiritually. Most of them are too steeped in capitalism realism to be able to reflect on it or describe it, let alone criticize it.

—Evgenia

We’re thinking of doing a monthly book club and discussions on Substack Threads. Let us know in the comments if you’re interested.

Want to know more? Read Evgenia’s…

If be interested in the book club. Your description of the Red Bourgeoisie reminded me of Grossman’s Everything Flows when the the recently released prisoner of the gulag meets the person who denounced him as the denouncer is getting into a limo.

I also liked your recent mention of Platanov.

Thanks for the thoughtful article. I downloaded McDonell's book and plan to read it soon. Can you recommend any Russian works in a similar vein?

The way you describe him and his writing made me think back to Lewis Lapham, so I asked ChatGPT to summarize Lapham's critiques of the "meritocracy". A lot of parallels!

🎭1. Meritocracy Is a Myth That Masks Inherited Power

"The American faith in meritocracy is a magnificent alibi for privilege."

Lapham argued that the idea of a "level playing field" is a convenient fiction. He believed American elites used meritocratic language—“hard work,” “talent,” “education”—to mask systems of inheritance, social connections, and cultural capital that reproduce privilege across generations.

Elite prep schools and Ivy League colleges, he pointed out, claim to admit based on merit but disproportionately select from the same wealthy families.

Success, in his view, was more about being “born into the right house” than innate ability.

🧳 2. The Ruling Class Has Simply Rebranded Itself

In Money and Class in America, Lapham describes the postwar elite as a new aristocracy disguised as self-made men. While European aristocrats flaunted their inherited status, the American rich pretended to have earned it.

The nouveau riche co-opted the language of merit to make their power seem legitimate.

He noted that “the ruling class... now wears the clothing of egalitarian democracy while arranging the laws to serve its own convenience.”

🧠 3. Elite Education Is a Gatekeeping Mechanism

He relentlessly mocked the Ivy League as an elaborate credentialing system for the upper class.

The purpose of elite education, he said, wasn’t to cultivate intellect but to signal status and provide access to elite networks.

Lapham saw prep schools and Ivies not as meritocratic ladders but as “courts of entry” to an exclusive club.

“The SAT is merely a secret handshake.”

🗣️ 4. The Language of Meritocracy Silences Class Critique

Lapham believed that the American obsession with meritocracy discourages real conversations about inequality.

If the poor are poor because they didn’t try hard enough, then the system doesn’t have to change.

The myth lets the winners moralize their success and blame the losers.

🪞 5. America Worships Winners, Not Virtue

He often mocked the way society confuses wealth with wisdom, success with virtue, and celebrity with credibility.

“Wealth confers prestige, and prestige substitutes for virtue.”

The meritocracy, in this sense, becomes a religion of appearances, not substance.